Iranian Hackers Lurked in Middle East Infrastructure for Two Years

A cyber espionage campaign, allegedly backed by the Iranian government, infiltrated a critical national infrastructure target in the Middle East and maintained access for almost two years. The attackers reportedly exploited VPN vulnerabilities and deployed custom malware to achieve their long-term intrusion.

A long-term cyber intrusion, lasting nearly two years, has been linked to an Iranian state-sponsored group. The target? Critical national infrastructure (CNI) located in the Middle East.

According to a new report from the FortiGuard Incident Response (FGIR) team, this activity spanned from at least May 2023 to February 2025. They describe it as "extensive espionage operations and suspected network prepositioning." Think of that last part as setting up camp inside the network, ready for future moves.

The FGIR team says this attack shares similarities with the tactics of a known Iranian group called Lemon Sandstorm (also known as Rubidium, Parisite, Pioneer Kitten, and UNC757).

This isn't Lemon Sandstorm's first rodeo. They've reportedly been active since at least 2017, targeting sectors like aerospace, oil and gas, water, and electricity in the US, Middle East, Europe, and Australia. Industrial cybersecurity firm Dragos notes they've exploited VPN vulnerabilities in Fortinet, Pulse Secure, and Palo Alto Networks to get their foot in the door.

Just last year, U.S. cybersecurity and intelligence agencies fingered Lemon Sandstorm for using ransomware against organizations in the U.S., Israel, Azerbaijan, and the United Arab Emirates.

How the Attack Unfolded

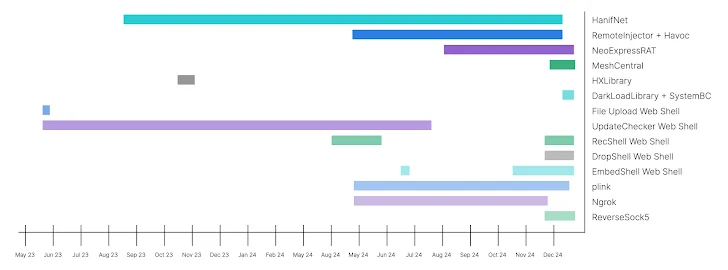

Fortinet's analysis shows the attack on the CNI victim unfolded in four phases, starting in May 2023. The attackers adapted their tools as the victim tried to fight back:

- May 15, 2023 – April 29, 2024: Initial access via stolen VPN credentials, dropping web shells, and deploying backdoors (Havoc, HanifNet, and HXLibrary) for persistent access.

- April 30, 2024 – November 22, 2024: Solidifying their position with more web shells and a backdoor (NeoExpressRAT). They used tools like plink and Ngrok to dig deeper, steal emails, and move laterally to the virtualization infrastructure.

- November 23, 2024 – December 13, 2024: Responding to the victim's defenses by deploying even more web shells and backdoors (MeshCentral Agent and SystemBC).

- December 14, 2024 – Present: Attempting to regain access by exploiting Biotime vulnerabilities (CVE-2023-38950, CVE-2023-38951, and CVE-2023-38952) and launching spear-phishing attacks to steal Microsoft 365 credentials.

It's interesting to note that Havoc and MeshCentral are open-source tools. Havoc is a command-and-control framework, while MeshCentral is for remote monitoring. SystemBC, on the other hand, is a common malware often used before ransomware attacks.

A Closer Look at the Malware Arsenal

Here's a quick rundown of some of the custom malware and open-source tools used in the attack:

- HanifNet: A .NET executable that pulls commands from a command-and-control server.

- HXLibrary: A malicious IIS module that retrieves text files from Google Docs to find the C2 server.

- CredInterceptor: A DLL-based tool for stealing credentials from the Windows Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) process memory.

- RemoteInjector: A loader for executing payloads like Havoc.

- RecShell: A web shell for initial reconnaissance.

- NeoExpressRAT: A backdoor that gets its configuration from the C2 server, possibly using Discord for communication.

- DropShell: A web shell with basic file upload capabilities.

- DarkLoadLibrary: An open-source loader used to launch SystemBC.

The connection to Lemon Sandstorm comes from C2 infrastructure (apps.gist.githubapp[.]net and gupdate[.]net) previously linked to their operations.

Fortinet believes the victim's Operational Technology (OT) network was a major target, based on the attacker's reconnaissance. However, there's no evidence they actually made it into the OT network itself.

The report suggests the attack involved hands-on keyboard activity from multiple people, judging by command errors and a consistent work schedule. They may have had access to the network as far back as May 15, 2021.

"Throughout the intrusion, the attacker leveraged chained proxies and custom implants to bypass network segmentation and move laterally within the environment," Fortinet said. "In later stages, they consistently chained four different proxy tools to access internal network segments, demonstrating a sophisticated approach to maintaining persistence and avoiding detection."